Indian Twitter and its Anti-Nationals

My work in collaboration with Joyojeet Pal originally appeared as a Wire reprint and a blog.

Social Media coverage by the Founding Editor of the Wire Siddharth and retweets of Joyojeet’s tweet by Shehla Rashid, Ankit Lal, etc.

Recent references to the farmer protests as “anti-national”, including by major political actors, raises questions of how the term has been used. Much recent work has considered ways in which the notion of being antinational has been attached to various forms of dissent (1) (2) (3), but also in general as part of an overall increase in polarization in the Indian political environment (4). The term “anti-national”, used typically to suggest seditiousness in the object of the slur, is increasingly used by political parties against each other, and against individuals whose positions they are at odds with.

We examined the use of the term anti-national and its various synonyms and derivatives by politicians across parties and states in India between 2016 and 2020 and present the results here. We used a database of tweets from about 37,000 Indian politicians, public figures, journalists, and media houses from the NivaDuck database (5). We considered the time period from Jan 1 2016- Dec 17 2020, and used variants of the term anti-national either in text or as hashtags, using a substring match (anti-national”, “anti national”, “antinational”, “anti_national”). For Hindi, we used देशद्रोही, and its substring variants as matches. We did not include direct translation for synonyms in other languages. This method is very conservative and excludes various other messages that may include the sentiment, but not the precise terminology, but for our purposes it gives higher precision despite lower recall, and thereby gives us a sense of how the term’s usage has expanded among public figures. For our purposes, we do not look at the explicit use of these terms among casual Twitter users, however, our retweet analyses do offer some sense into how the general public reacts to these terms.

We found approximately 100,000 tweets that were either tweets or retweets, of these, about 37,000 were original tweets. Within this sample, the single largest language represented was Hindi, with about 20,000 tweets, followed by English, with about 9000 tweets, and all other regional languages comprising the rest. The non-English tweets were counted primarily for the use of hashtags using Roman script.

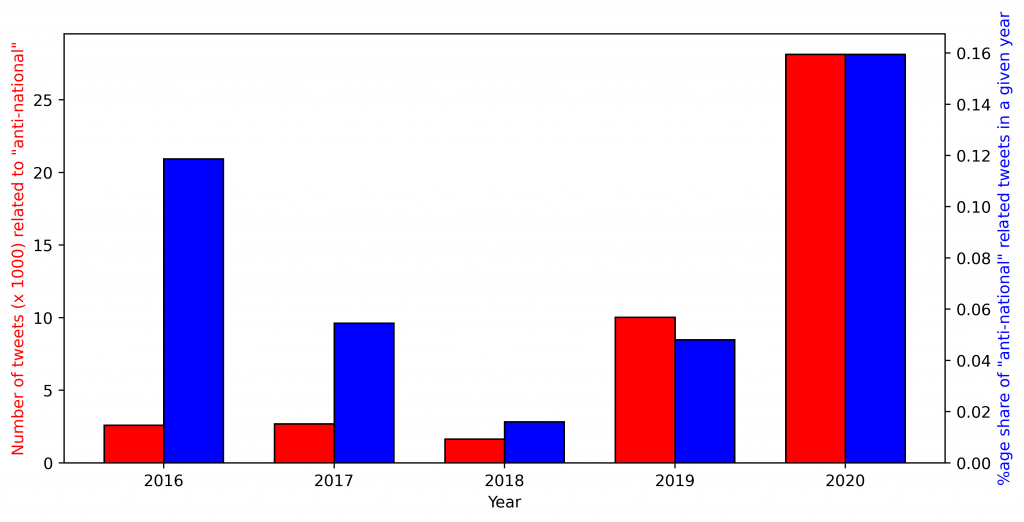

First, we find that the use of the term is increasing, at a proportion slightly higher than the corresponding increase in tweeting by politicians, public figures etc. We find that during elections, there is an increase in the use of the term in tweets.

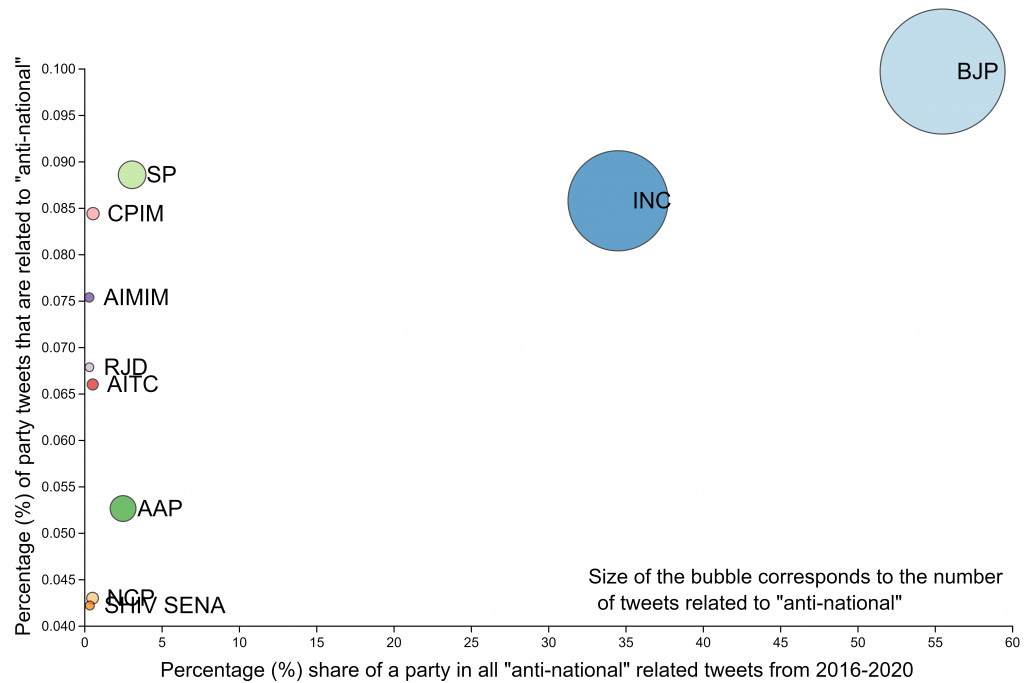

We see that counter to notions that the term is used largely by the ruling party against its detractors, the use of “anti-national” is seen across parties, but with subtle differences. BJP politicians use the term more than all the other major parties, both in terms of total scale. This is in part because BJP politicians are most numerous on social media, but the BJP also leads in terms of the percent share of total tweets that have the term in it. It should be noted that the specific term itself only shows up in 0.1% of all tweets, but since this methodology focuses on the specific terminology, the number as a share of the whole is expectedly small.

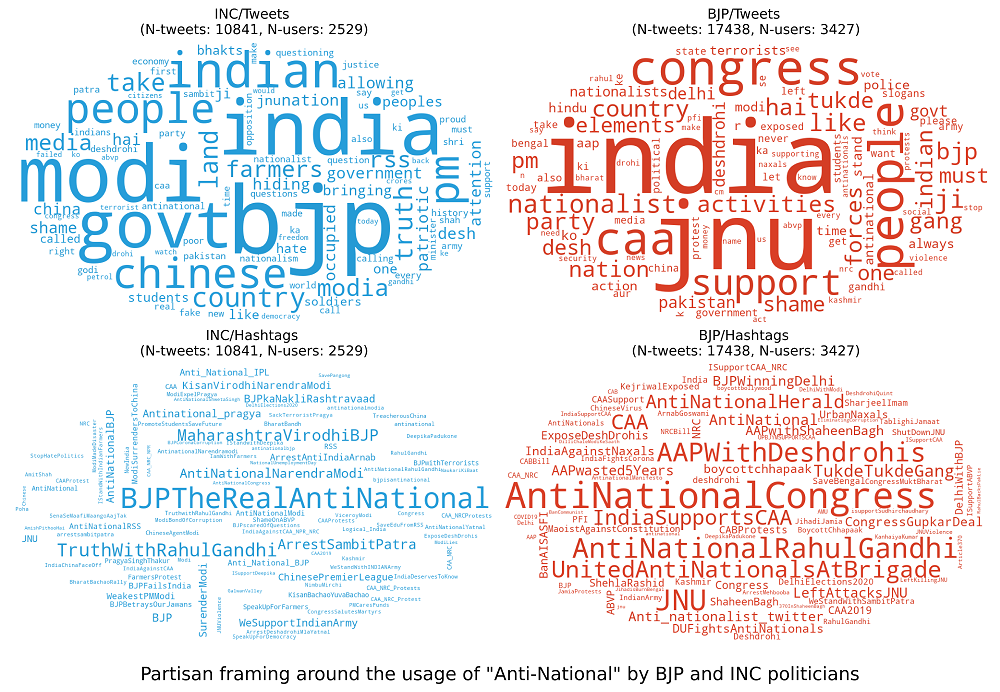

The interesting difference in patterns of use is that while BJP politicians use the term to refer to various individuals and causes, in addition to parties, the other parties, when using anti-national almost exclusively use it in reference to the BJP party itself. We see in figure 2, for instance, that while both the BJP and INC attack each other using anti-national, the INC focuses on the party, the RSS and a few key leaders including Modi, Sambit Patra and Amit Shah, or uses terms to target the BJP, the BJP goes after the INC, AAP and also the entire opposition (such as the trending of the hashtag #UnitedAntiNationalsAtBrigade, referring to a group of non-BJP leaders who met in Bengal in early 2019).

For the BJP, the most used term is not the name of another party, but rather JNU, referring to the Jawaharlal Nehru University, and the top issue on the BJP side was the CAA, whereas for the INC it was related to Chinese incursion into Ladakh in 2020. The BJP also uses terms such as tukde tukde and terrorist much more than the INC. Both parties use “shame” as the major emotion verb in messaging about anti-nationals. The INC uses “truth” as a value adjective much more than the BJP.

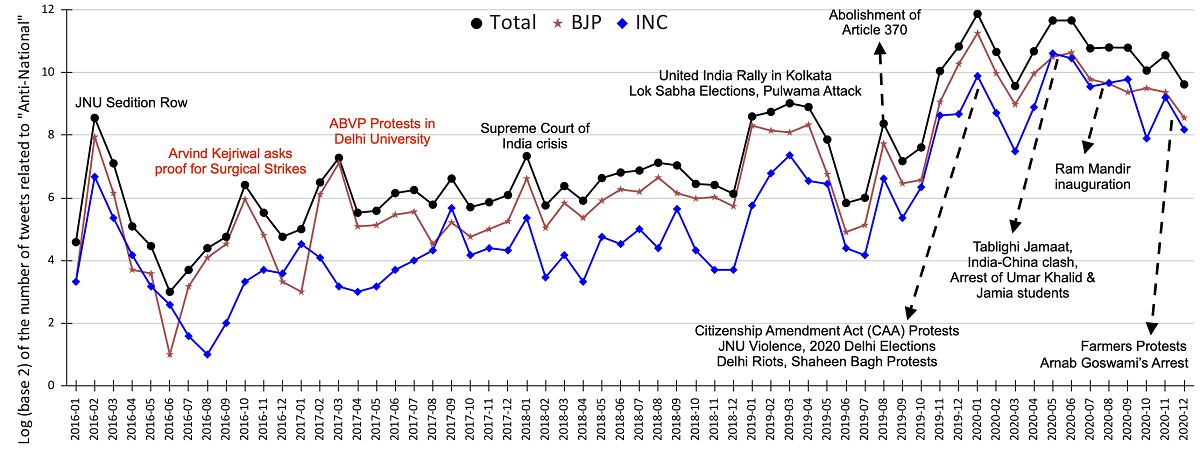

Comparing the INC and the BJP, we see a pattern of peaks marking the points when parties talk about ‘anti-nationals.’ In figure 4 below (log scaled) we see that the first peak of conversation was around the 2016 JNU sedition row, but that consistently, the two parties tend to talk about the subject of anti-nationals roughly around the same time, although the target of the tweeting differs. The first instance where BJP uses anti-national much more than the INC was in late 2016 when BJP leaders targeted AAP for asking for proof of the ‘surgical strikes’ that were announced in September 2016. Here, the terms of anti-national were largely used against those who questioned the official version of events, including specifically calling Arvind Kejriwal a traitor.

We see that the most dramatic increase in the use of ‘anti-national’ happens in 2019 starting with the abolishment of Art 370, and peaking thereafter during the CAA protests. However, it is important that post-2019, there is a new and more consistent use of ‘anti-national’ on major issues that gather traffic on social media. Thus both the Ram Mandir inauguration and the Farmer protests in Delhi saw more instances of politicians referring to people as ‘anti-national’ than for instance the aftermath of the Pulwama attack.

Targeting vs Using

There are differences between who is targeted by tweets mentioning anti-nationals. While the majority of targeting is aimed at politicians or journalists, there are a number of citizens in various forms of public life who have been targeted as anti-nationals. Most targeting takes place within the text of the tweets while separate hashtags are created to target individuals only when there is a coordinated attempt to attack. Such targeted attacks tend to be issue-based, examples include attacks on Dalit issue activists Dilip Mandal, Jignesh Mewani, on Kashmiris Shehla Rashid, Mehbooba Mufti, on industrialist families including Adanis and Ambanis, on figures or issues associated with the Hindu-right politics including Godse and Savarkar, and with issues or individuals associated with Muslims, including Tipu Sultan and the Mughals.

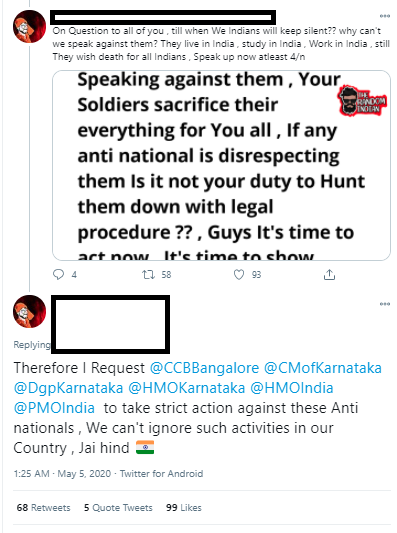

Individuals can be targeted or simply co-mentioned in a tweet. The handle of the Home Ministry or of law enforcement handles such as City Police handles or Chief Ministers’ offices are often mentioned in ‘anti-national’ tweets with the intention of “bringing to the attention” to institutions of power individuals who are being targeted. We see an example in figure 5 below.

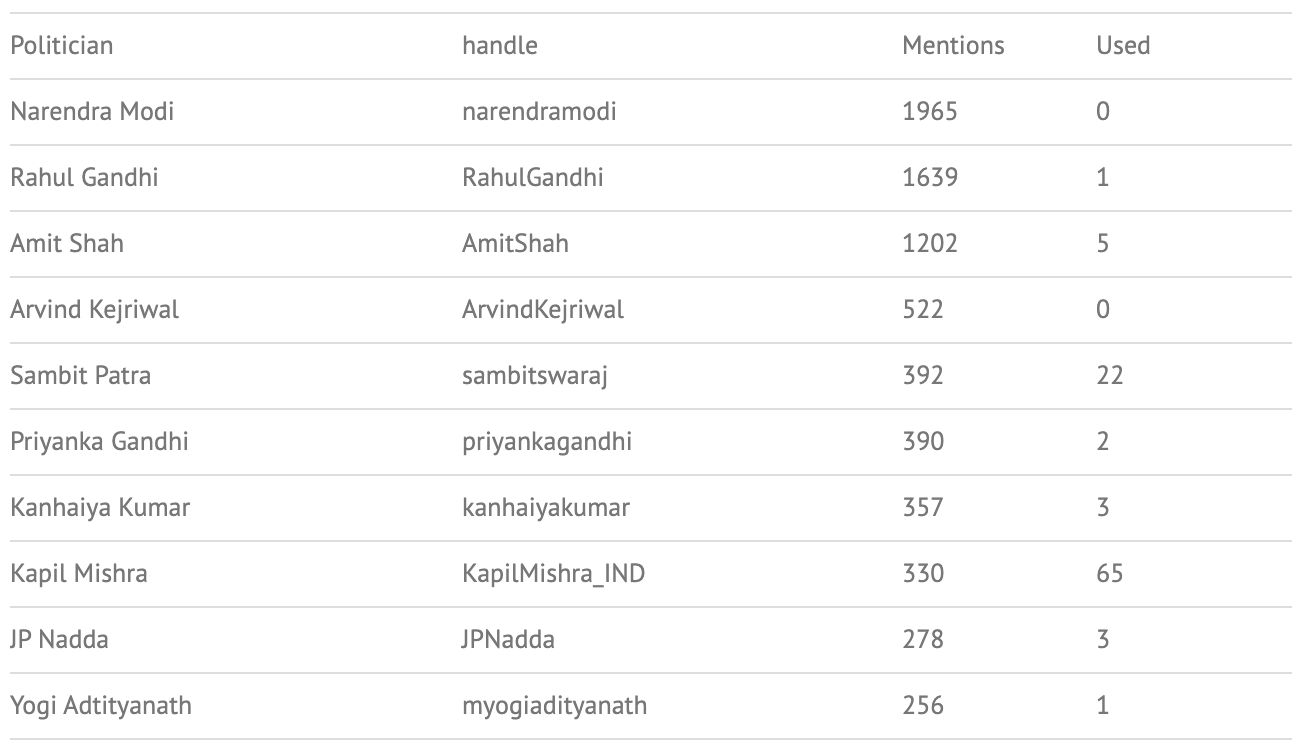

In the case of Narendra Modi, he is both highly targeted, but also co-mentioned, when an individual poster tries to bring an individual or issue to the attention of the PMO. Similarly, Amit Shah is both targeted and co-mentioned. However, opposition figures such as Rahul Gandhi, Mamata Banerjee etc are mainly targeted and not co-mentioned.

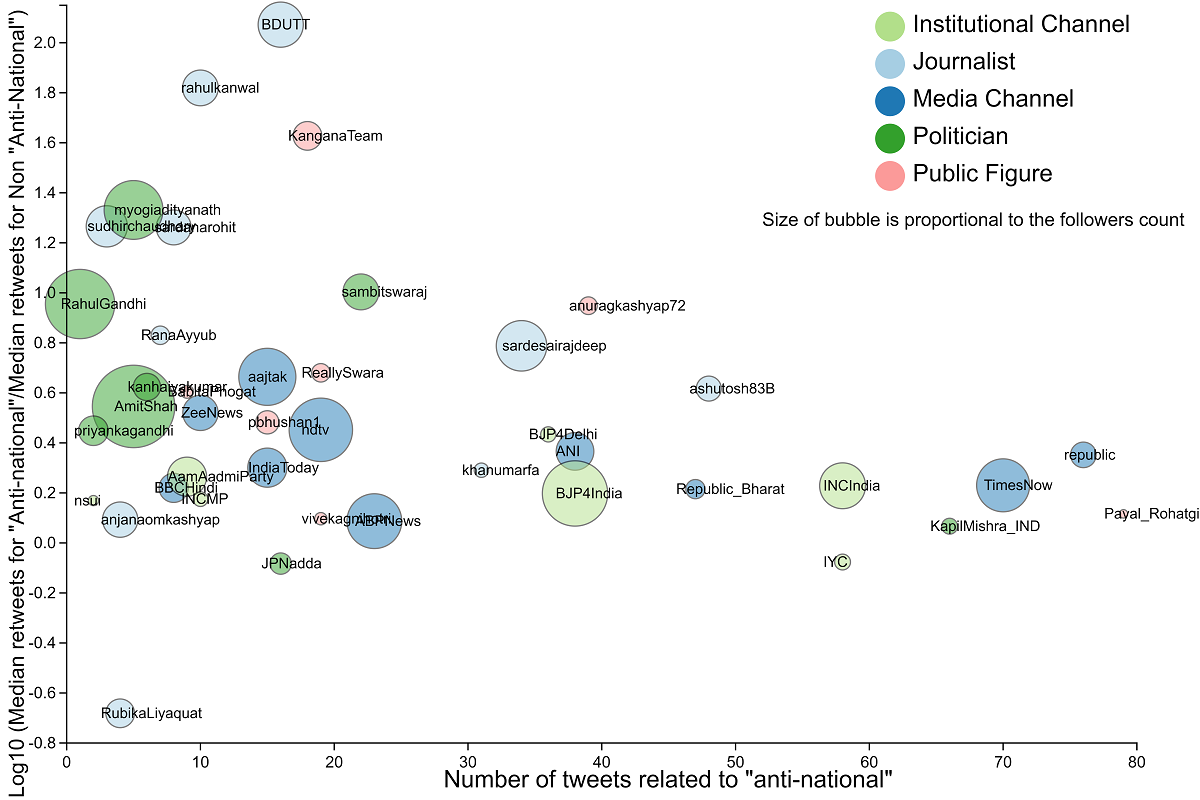

We see an important pattern in Table 1 above — that getting mentioned in a tweet about ‘anti-national’ does not correspond to the use of the terminology. We see for instance that Narendra Modi and Arvind Kejriwal have never used the exact term in tweets, while Rahul Gandhi and Yogi Adityanath, each of whom have sent at least one widely viral tweet with that wording, have both used the term just once each. The only co-mentioned politicians who also use the term significantly are Sambit Patra and Kapil Mishra. Importantly, for almost all these politicians, when they do tweet with the term ‘anti-national’ in their tweet, they get significantly more retweeted for those tweets than their typical other tweets (median retweet count). In fact, as we see in Figure 6, this is a generally reliable pattern across politicians, media personalities, and public figures alike — as ‘anti-national’ is mentioned, the median rate of retweet increases.

We also see two important patterns here. First, a small number of accounts tweet the terminology out significantly more than most others – @republic, @Payal_Rohatgi, @TimesNow, and while these do see a significant increase in retweets when the subject matter is ‘anti-national’ related (the figure is on a log scale), a few of highly influential accounts including journalists Barkha Dutt and Rahul Kanwal and actors Kangana Ranaut and Anurag Kashyap get much more attention.

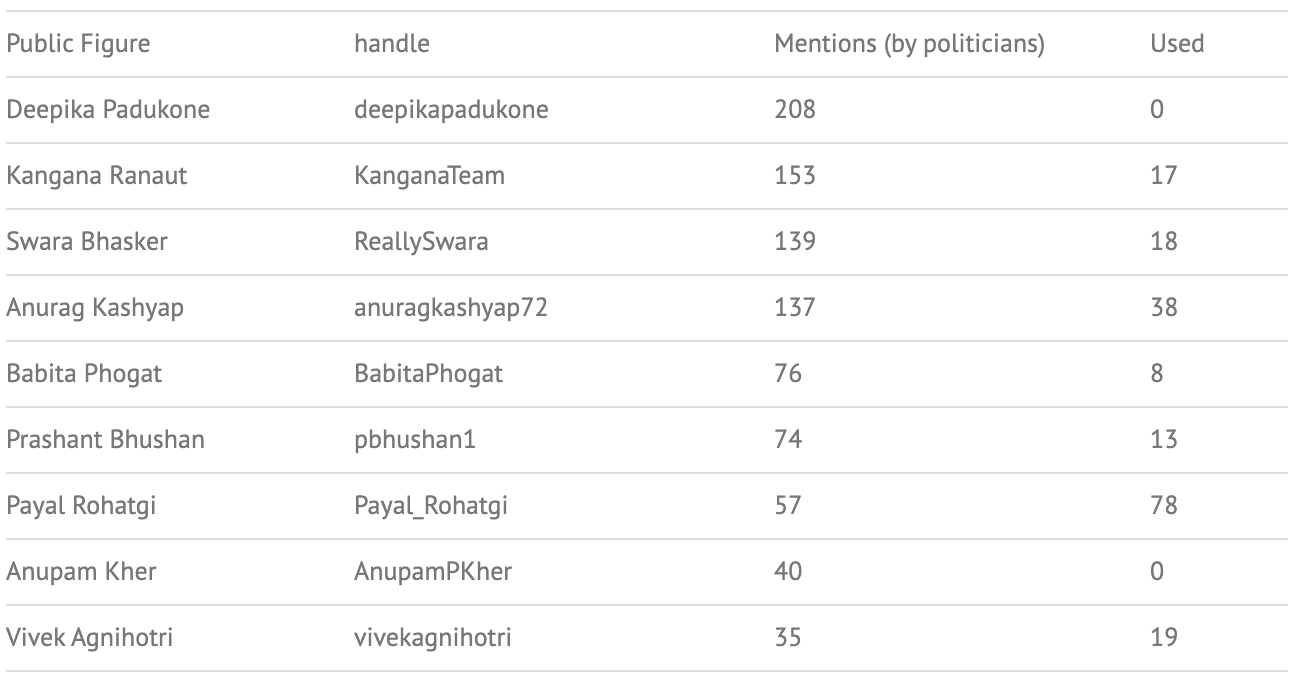

Among public figures mentioned in ‘anti-national’ Tweets we see the most concerted targeting was aimed at Deepika Padukone, who has never actually used the term in a tweet. Likewise, Anupam Kher tends to be co-mentioned, but has not used the term himself. While Kangana Ranaut also gets significant mention, a share of those are just co-mentions in which the actual target is someone else, the co-mention being aimed at garnering more attention. Anurag Kashyap is both targeted, but also pushes back against the anti-national term a lot in his tweeting.

While individuals are frequently targeted, so are specific themes. For instance, West Bengal is frequently targeted alongside the term ‘jihadi’, used to refer to the Muslim population in the state and proposing they support the ruling TMC government. Likewise, support for birthday celebrations for Mysore ruler Tipu Sultan are presented as anti-national.

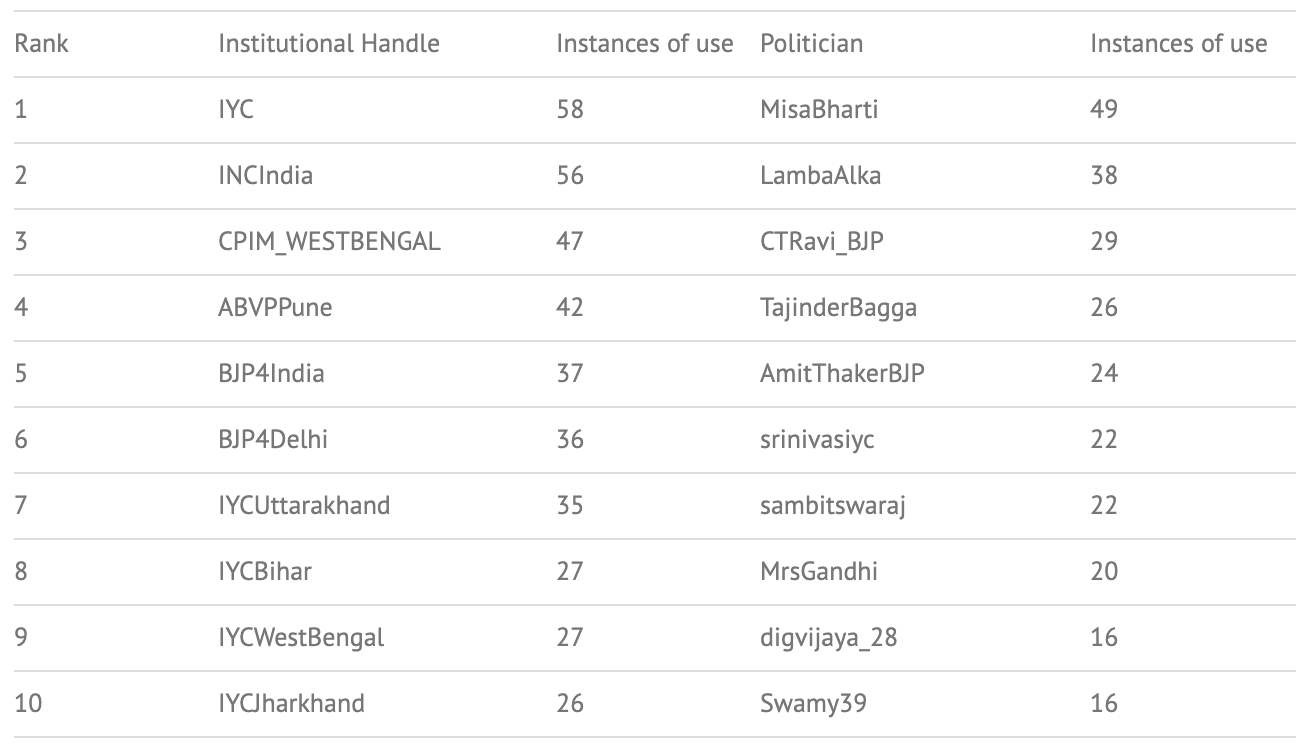

From among frequent users of ‘anti-national’ we find that the most active users of the terminology tend to be mid- to low-level politicians, usually those with less than 10,000 followers, who originate such tweets. In general, higher-ranking politicians eschew the term. In table 3 below, we see the major politicians and party handles that use the term the most.

We see here that there is a spread of organizations on the BJP and INC sides that are frequent users of the anti-national terminology. The Indian Youth Congress handles from various states are among the most aggressive users of the language. Among politicians, Sambit Patra, Subramanian Swamy and Digvijay Singh use the language a lot — and while Singh tends to use it against the BJP, Patra and Swamy also use it against casual citizens. From among the other politicians who use the term a lot, Misa Bharti and Alka Lamba tend to push back against the use of the term, rather than use it against others.

References

- Ansari, R. and S. Riaz, Construction of ’Anti-National’: Framing and Othering Discourse in Indian Media. Global Media Journal, 2020. 18(36): p. 1A-8A.

- Mehta, N., Redefining ‘Azadi’in India: the prose of anti-sedition.South Asian History and Culture, 2016. 7(3): p. 322-325.

- Rogenhofer, J.M. and A. Panievsky, Antidemocratic populism in power: comparing Erdoğan’s Turkey with Modi’s India and Netanyahu’s Israel.Democratization, 2020. 27(8): p. 1394-1412.

- Sinha, S., Fragile hegemony: Modi, social media and competitive electoral populism in India.International Journal of Communication, 2018. 11(2017): p. 4158-4180.

- Panda, A., Gonawela, A., Acharyya, S., Mishra, D., Mohapatra, M., Chandrasekaran, R., Pal, J. NivaDuck – A Scalable Pipeline to Build a Database of Political Twitter Handles for India and the United States. SMSociety’20: International Conference on Social Media and Society July 2020 Pages 200–209 https://doi.org/10.1145/3400806.3400830.